A new report from the District Attorney’s Office has concluded that the vestiges of slavery, redlining, and the War on Drugs are still present in Philadelphia’s legal system and disproportionately impact Black communities.

Titled “Racial Injustice Report: Disparities in Philadelphia’s Courts from 2015 to 2022,” the report mined over 290,000 criminal cases from the last eight years to reveal that Black people are overrepresented at every stage of the legal system, from car stops and pedestrian stops to incarceration.

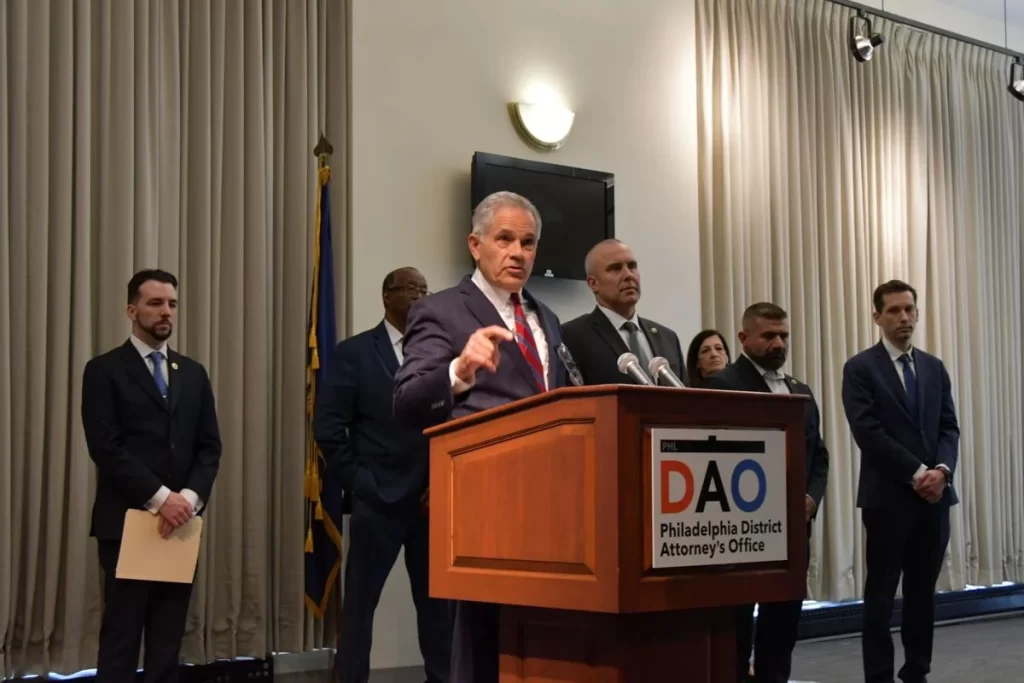

District Attorney Larry Krasner released the report Monday at a news conference outside Eastern State Penitentiary, where he was joined by antiviolence activists, and formerly incarcerated men, who spoke against a backdrop of building blocks meant to depict the uptick in Black incarceration rates over time.

The spirit of Juneteenth pervaded the event as City Councilmember Jamie Gauthier spoke about the duality of the moment: It was great to see a full crowd of community members, Gauthier said, but also a reminder of how true freedom for Black Americans is a moving goalpost.

“We see the impact of slavery all around us. Black Philadelphians … endure racism that’s baked into the very foundation of our city and society,” she said. “The government never atoned from its original sin of slavery … [and] lawmakers have enacted and encouraged policies that subjugated Black residents to second-class citizenship.”

Gauthier said she was referring to policies that have left majority Black neighborhoods in Philadelphia with disinvestment, from laws that withheld mortgages in Black communities in the 1960s to the recent closures of recreation centers, public schools, and community gardens.

The new report from the District Attorney’s Office aimed to connect the dots between the overt racism of the last century and the implicit, structural racism many say permeates Philadelphia today.

“Past policy actions grounded in racism … set neighborhoods on a long downward trajectory,” the report reads, “and continue to harm the futures of residents by putting them at higher risk of experiencing crime and violence.”

Krasner said the goal of the report was not to offer an immediate corrective agenda, but to “put numbers to a problem.”

“We don’t know what needs to be done,” the DA said. “But the only way to fix a problem is to measure it.”

Here are four takeaways from the report.

Philadelphia’s history is intertwined with the prison system

The report outlines how the foundations of the legal system started as a means of enforcing slavery, before evolving into something that still places Black people into state supervision at disproportionately high rates.

Philadelphia played a major role in mass incarceration’s origin story: Eastern State Penitentiary was the first to use solitary confinement on a majority Black inmate population, serving as a model for the modern-day prison.

The myth of the “super predator” was coined by then-University of Pennsylvania professor John DiIulio. And former District Attorney Lynne Abraham, dubbed the “Deadliest D.A” was known for advocating the death penalty in many murder cases and seeking life sentences for juveniles convicted of murder.

“My predecessors — certainly every single one I observed, perpetuated racism,” Krasner told reporters. “It has always been the responsibility of every prosecutor in the United States to remediate that because their sworn oath is to seek justice, not racism, hatred, [or] bigotry.”

Black Philadelphians are overrepresented at every stage of the criminal justice system

Black Philadelphians are overrepresented at every stage of the legal system when compared with their white counterparts, the report found, starting with their likelihood of being stopped and arrested.

Black and white people make up similar proportions of Philadelphia’s population — 38% and 34% respectively — yet Black people are 1.5 times more likely to be stopped by an officer, the report said.

Black people account for nearly two-thirds of arrests from these stops, though “police are most likely to find contraband when searching white people and least likely to find it when searching Black people,” said the report.

That’s because stop-and-frisk activity — which has fallen overall following stipulations that data be made public — is concentrated in the city’s majority Black and Latinx neighborhoods, such as Kensington, Strawberry Mansion, and North and West Philly, according to the report.

“This difference may signal racial bias in who the police choose to search,” the report said, dovetailing with a 2010 lawsuit from the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania that alleged police officers were stopping Black people for reasons that didn’t meet the legal requirements for reasonable suspicion.

Black Philadelphians are more likely to be charged with felonies

Black Philadelphians are charged at a higher rate than any other racial or ethnic group for the majority of criminal offenses, except for drug possession and drug dealing.

The report attributes the reduction in drug charges against Black Philadelphians to Krasner’s policy of not prosecuting low-level cases of marijuana possession if a person is in addiction treatment.

Still, more than half of Black people who entered the criminal justice system from 2015 to 2022 were charged with felonies, compared with about a quarter of white people charged with similar crimes.

“The perceived seriousness of an alleged crime impacts every other phase of the criminal legal system, including bail, eligibility for diversion, and sentencing,” reads the report.

The high proportion of felony charges may make Black people in the criminal justice system ineligible for diversion programs, which often exclude people with more serious charges, and it may also make them more likely to be detained pre-trial.

The path forward: Collaboration, acknowledging structural racism

The report’s recommendations are heavy on the need for collaboration with community antiviolence groups, public officials, formerly incarcerated people, and police officers.

The report suggests that city agencies acknowledge that structural racism exists, while also working with Black and brown communities to improve their neighborhoods through the greening of vacant lots, the revitalization of blighted properties, and a curb on illegal dumping — all interventions demonstrated to reduce violent crime.

“It is tempting for individual justice agencies to absolve themselves of responsibility for change by claiming that the problems are created elsewhere and simply inherited,” the report concluded. “To avoid this, all agencies must become interested in the root causes of disparity.”

Source: The Philadelphia Inquirer